france, july 1950:

The lengthening shadows of a July afternoon, reach across from the makeshift platform to Luxeuil abbey. The crowds hush, the tannoy whistles momentarily as one of the leading politicians of the age rises to speak. Around him are many eminent European statesmen. He has called them to this abbey in central France for a conference – or more precisely, a piece of sacramental political theatre. This is 1950, and Robert Schuman is about to call up the spirit of a 6th-century Irish monk in the fight to save Europe from an apocalyptic Third World War. Saint Columban, who founded the abbey, was eventually extradited from the region as a trouble-making immigrant. And now, thirteen centuries later, a French Foreign Secretary will use this Irish émigré as a poster child for the most daring political project since the league of Delos unified the Greek city states. He is clearing his throat and approaching the microphone. In that pause between breaths, the politicians of Europe hear a collared dove cooing somewhere very near them in the lime trees. For the briefest of moments, they look up – as all Europe looks up. And they together discern the sound that a few years back they thought they would never hear again. It is the dove of peace.

We shall return to this moment in chapter 16. But suffice to say for now, the improbability of this event, its epoch-making results and the personalities involved form the grist of our story. And with that said, let us now begin by fast-forwarding to the same month 66 years later.

Britain 2019

In the French language, everything that is good is feminine. But even they refer to our departure from the European Union as le Brexit – which is rather touching when you think about it.

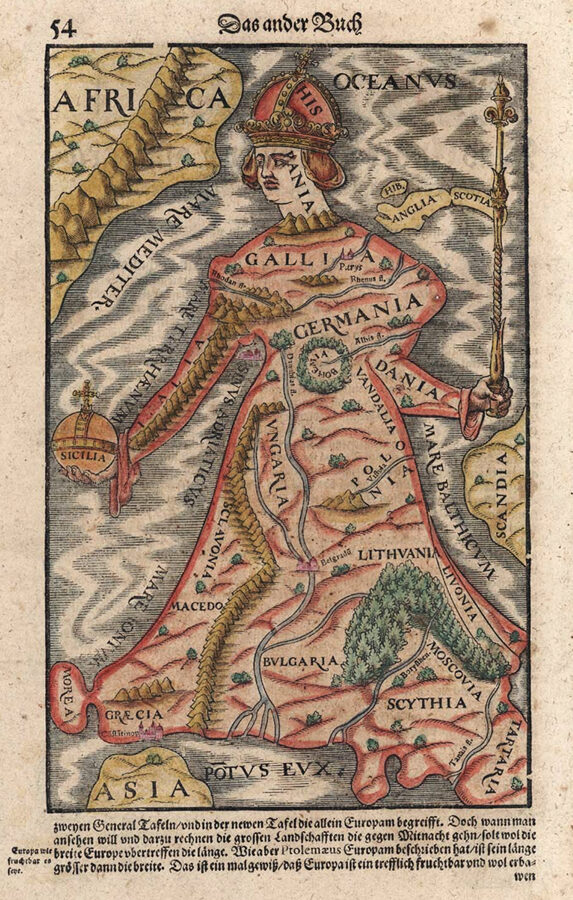

But for good or evil, Britain is leaving the EU in 2021. And during the long and acrimonious divorce, I decided to do what I did not have time to do during the furore of 2016. I wanted to take a look through the long telescope of history and to ask the questions that I could not quite articulate during the hubbub of the referendum. Like others, I found it hard at times to differentiate between being European and being in the E.U. But even then, I still wanted to understand what, if anything, was so special about this group of nations that we call Europe. And more than that; what is the philosophical and historical consciousness that formed such a singular culture and civilisation? And how many strands of memory; sociological, legal, ethnic, historical and religious bind us together? And of course, how much of this, if anything, would be affected by our leaving? The islands of Britain have always stood in a peculiar relation to their neighbours for good or ill, and sometimes both at once. But how much have we Britons helped to make them who they are over the last 2000 years? And how much have they made us who we are?

In 2017 these questions, and many others haunted me. I, like many, had felt deeply inadequate to vote on something so momentous when I was so ignorant. And even though the moment has passed, I still believe this book could go some way to help us post-Brexit-Brits to appreciate, not just our own unique position in the European story, but also the depth and richness of our neighbours’ stories that still define us. Like the French philosopher Paul Ricoeur1, my hope is, to achieve some level of ‘self-understanding by means of understanding others.’2 An island, like ours, on the edge of a great landmass must not only exalt in but also ‘conquer a remoteness’3 of outlook. This ‘Anglo-Celtic archipelago’ must overcome a dual distance; firstly, between itself and its European partners, and secondly, between itself and its own history. Whatever the next decade will be for us, surely it cannot be a time of geographical and historical parochialism. A regiment may move some distance without its allies, but it cannot be severed from the supply train at the same time. Some speak as if our only concern should be economic. Brexit will certainly do many things. And one might be to shake us out of our present rootless amnesia and send us searching for the great supply train of our rich history. People with dementia cannot plan for the future, says Philosopher Alain de Botton. Herein lies a great part of our challenge – to reverse-engineer our cultural amnesia.

COLUMBANUS (543-615)

This book makes tentative steps to address both tasks. My modus operandi may seem unorthodox at first glance but there is method in it. I want to follow two eyewitnesses – an Irish monk and a French politician – who, to my mind at least, form key historical markers at either end of our European consciousness. This consciousness first arose after the collapse of the Roman Empire, and then finally took root in the rubble of two nigh-apocalyptic world wars. In observing these two witnesses within the crucible of two ‘dark ages’4, we catch a greater perspective of our own dilemma.

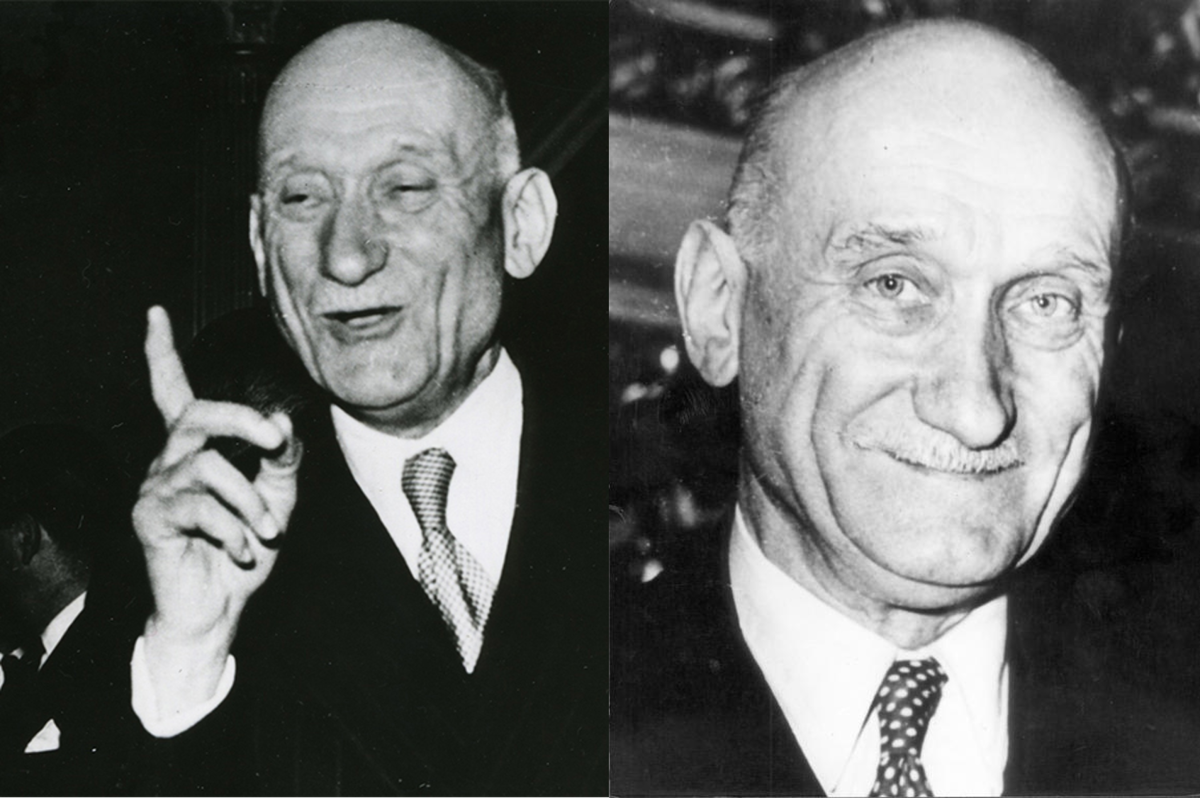

These eye-witnesses are two extraordinary, yet relatively unknown men, who by their tenacity and – and dare I say – humility, played key roles in saving the European civilisation of their day. We talk about it, but these men literally moved the hour-hand of history. The first, as already mentioned is the 6th-century Irish monk Columban who often found himself acting as a reluctant statesman. The second is the 20th-century French statesman Robert Schuman who very nearly became a monk.

This book will be our Tardis and in it we will travel, chapter by chapter, up and down the time corridor like Dr Who; back and forth between these two ‘Dark Ages’, two epochs, and two unsung heroes. Caught, as they were between the great hinges of history, and as we are – between amnesia and memory – maybe we shall eventually return to the 21st century with a new perspective.

The first is Columban or Columbanus (543-615), patron saint of bikers and bad boy of medieval monasticism. More dissenter than revolutionary, Columban was a poet, preacher, prophet, polemicist, scholar, saint.5 Alongside Charlemagne, Columban has been referred to as the greatest man of the Middle Ages.6 His surviving literary corpus alone places him head and shoulders above his contemporaries as the first great Irishman of letters.7 But it was as a monastic founder that we owe him the greater debt. He undertook a voluntary exile from his homeland and, through a missionary odyssey in France, Germany, Austria and Switzerland, finally came to the valley in Italy that Hemmingway declaimed ‘the loveliest in the world.’8 The five houses he founded on the continent multiplied to perhaps as many as two hundred Schottenkloster (Irish Monasteries) that became so critical in the preservation and transmission of scholarship, faith and literacy over the next two crucial centuries. In fact, nearly all surviving 7th and 8th century manuscripts from continental Europe are indirectly due to this one man’s monastic legacy.9

He was also the first of his countrymen to express an Irish sense of identity in writing and the first to articulate for us the concept of a united Europe – making reference to Totius Europea flaccentis augustissimus – ‘all of decaying Europe’ – in a letter to the Pope.10 At about the same time, and using a biblical metaphor11 in a letter to the disgruntled Frankish bishops, he even gives a Christian basis for a supranational understanding between European nations. ‘We are all members of one body, whether Franks, or Britons, or Irish or whatever our race.’ So even as far back as 600AD, when Europe was still reeling from the barbarian migrations, and 50 years of plague that halved its population, we have this Irish immigrant claiming openly that that we Western Europeans already owe to each other allegiance that supersedes (though not replaces) racial and national identity. The historian Norman Davies wrote that Columbanus was ’the first to conceive of Europe as a civilizational unit centred on Rome.’12

According to the medieval scholar Dr Alex O’Hara, Columban was also ‘a forceful advocate for unity and tolerance in the divisive and violent world of his day. As an immigrant in the heart of Europe, he pleaded for toleration and accommodation. His example had a surprising influence on Robert Schuman, the post-war French foreign minister and architect of the modern European Union.’13

ROBERT SCHUMAN (1886-1963)

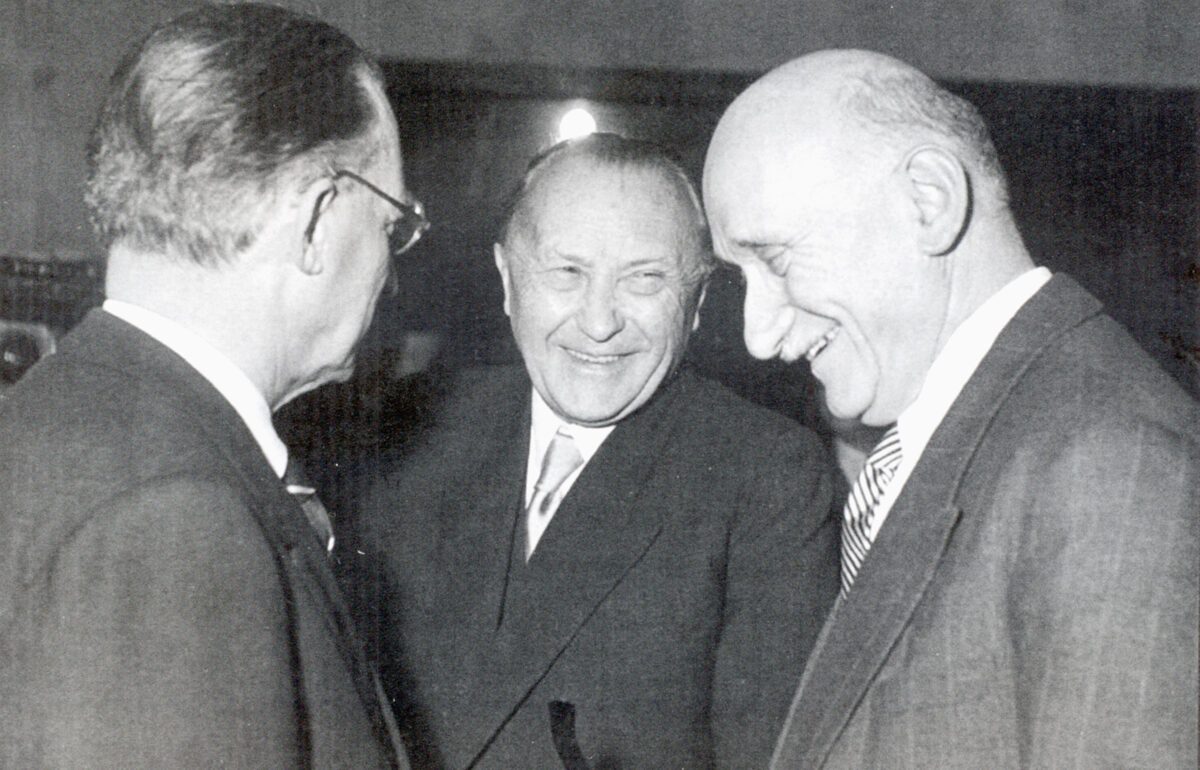

Robert Schuman (1886-1963), is the second ‘eyewitness’ whose life and times I wish to retell in this book. Schuman broke-out of Nazi incarceration after seven months in solitary confinement evaded the Gestapo in a daring solo escape across the Vosges Mountains, and then rose precariously after the war to become the French Foreign Minister and a founding Father of the EEC. His life, and that of two other co-founders14 form – at least from a historical novelist’s point of view – one of the most thrilling, moving and uplifting stories in any political history of any era.

Both Columban and Schuman were men of steely determination, neither ever married, and both came to the major work of their lives in middle age – which should give some of us hope. In some nebulous way they form the brackets, or bookends, of the European experiment; Columban at the inception of Totius Europea, and Schuman at the cementation of that pan-national fiction into a political and economic reality.

My Treatment of the

Subject

The ancient Greek writer Lucian advises that ‘the historian among his books should forget his nationality.’ But frankly this sort of position, which so characterised the enlightenment’s ‘prejudice against prejudices’15 has itself been given such a thorough drubbing in the twentieth century by scholars like Gadamer16 that one has to wonder whether the objectivity of the natural sciences is desirable, let alone possible in the humanities. Of course, I have tried to be as open handed with the sources as any red-blooded Englishman can be. And at the end of the day, Anglo-centrism is not a sin – not in the north of England at any rate! So, I bring a personal view about the evolution of western European civilisation, gazing intently, as I do, from the finibus extremis of that great landmass. I am conscious that my necessarily restricted western/Latin European focus might strike the broader scholar as too occidental – too reflective of a limited Enlightenment historiography – but where I am able, I will pay my respects to African influence (when discussing Anthony, the Desert Fathers, and Augustine in chapters 1 and 2, and the influence of the East in chapters 1 and 15.

I must also confess up front that I have not given equal wordage to the three great stages through which European culture has passed. The early stages of Pagan Rome and the Christian formation will receive vastly more wordage than the Enlightenment, partly because the latter is so well established, but also because the former is so little understood and appreciated among popular readers. This fact was rather visually highlighted to me in September 2018 when I was very kindly received at the House of European History in Brussels to film an interview with their director Dr Constanz Itzel. This extraordinary and brilliant museum is well worth a whole day’s visit, though the display ratios embraced the glaring bias of a European consciousness grounded in the Enlightenment. Having literally just travelled to Brussels from Aachen, the former centre of the (Carolingian) European Union twelve centuries previously, this did strike me as strange. It is rather like me pointing to a cake that is just coming out of the oven and exclaiming, ‘look! That oven has just made a cake!’ It acknowledges an important process in the cake’s production but shows that I have only just entered the kitchen. The fires of that industrial age certainly produced much heat and perhaps some light too, but in this book, I invite you to join me on a journey much further back; to sample the raw ingredients; as it were, to read the recipe books; perhaps even meeting one or two chefs.

I, as a northern Brit have come to this subject like Columban came to the continent; from de finibus extremis, the extreme fringe. And, like him, who journeyed south, east and west, so I too have struck out overland following my literary sources, looking for clues and narratives. My sources too, like Columbanus’ monastic band, are from diverse nations; Franks, Lombards, Scotti, and Alemani etc. With them I have crossed and re-crossed borders, heard their languages, enjoyed their cultures. In his excellent 2015 book Silk Roads, Peter Frankopan sought to re-centre European readers geographically.17 But the book you are holding attempts something comparable in the more fundamental realms of spirituality and philosophy.

And if there might be a European position from which to judge these things, or a western European one, perhaps we might claim it for Robert Schuman – ‘un homme de frontieres’ – born between France and Germany and who was a mix of both geographically, biologically, linguistically and culturally. In his person and his policies Schuman became the essential bridge between both at that critical hour. But even his developed position could not be seen as the bridge between the Enlightenment and the Romantics; between Kant and Hegel, for Schuman’s unassuming humanism – so extraordinarily assured and productive – was a stranger synthesis than any might guess. More medieval than modern; more rooted in Aquinas than Rousseau, more indebted to the socio-political writings of the popes than the purveyors of the new ideologies – he was an enigma to many in his day, and would probably be anathema to ours. Stranger still, his worldview was quite independently shared by his political counterparts in Italy and Germany. And in a paradox worthy of an epigram, it was the neo-scholastic humanism of Schuman, Adenauer and De Gasperi that made possible, what Javier Solana called, ‘the most innovative and successful integration process in the history of humankind.’18 In the midst of the modern amnesia, they reached back further and, in so doing, achieved something more progressive than the progressives ever dreamt, and more pragmatic than the pragmatists ever compromised for. Answering journalists’ questions after his famous declaration on May 9th 1951, Schuman quietly admitted before them all that it was ‘a leap into the unknown’ and yet he and others were able to lead the shattered nations through that unmarked door. This is a simplistic analysis and really one that is only intended to whet the readers’ appetites for something rich and unexpected.

Admittedly, these great men (and some very notable women who made and supported them) are not known well in Britain, and certainly not as they should be. When Alexander the Great reached Achilles’ tomb he said ‘happy are you, young man, for you will have the benefit of a great spokesman of your achievement.’ Alexander knew he couldn’t find a man of Homer’s ilk to write his own epitaph, and nor have Columban or Schuman through these efforts of mine. Columban was actually the first Irishman to be the subject of biography, and fortunately for us, it was written only shortly after his death. But alas, Schuman has no biography available in English at present – nor does De Gasperi.19

Columbanus’ summary of his own predicament are equally mine; ‘Who could listen to a greenhorn? Who is this bumptious babbler that dares to write such things unbidden?’20 I appreciate that our age demands specialisation but it also desperately needs synthesis too. Those of us blue-collar scholars who serve falteringly in the latter capacity will always face the accusation of superficiality, arrogance and dilettantism. To the specialist philosophers, historians21, sociologists, economists and others, I ask for special clemency. For I have trespassed through many areas of scholarship without so much as wiping my feet. This story – which we have either forgotten, or lost22 – must be retold, even if retold imperfectly. This I say with all humility for, unlike others qualified in these fields of study, I have so much more to be humble about.

To the general reader I also offer a very Columban’ confession; ‘talia confragosa loca’ - I come from a rough place. Far removed from the refinements of academia and the urban intelligentsia, I live in the far northwest of our island; a place where the Roman legions once defended the very borders of civilisation, and where the shepherds still count in old Norse. In fact, I live very literally in the shadow of England’s highest mountains, and in a figure, I wish to lead the reader – as I have led many other visiting friends over the years – along precipitous ridges and through upland environments unfamiliar to them.

I recently took my flatlander-Norfolk nephews along the infamous Striding Edge; a kilometre-long arête that yearly claims lives and where the adventurer is usually only ever one step from death. There is an under-path to the left and the right, but those who walk them inevitably only see half of the view. And I don’t mean this is merely an ascetic choice either, for each under-path has its own dangers too. I remember as a boy taking the under-path with my father during a winter white-out because the snow, ice and violent winds made the ridge too dangerous. But even in this event, we overshot the end of the ridge and found ourselves making a hazardously steep ascent in deep snow, arriving just under the summit. But for our ropes, ice axes and crampons, even the ‘safe’ under-path might have killed us.

But my main point here is that at various points, depending on your political or religious leaning, you might earnestly long for the under-path of your persuasion. And at those times you will inevitably feel the strength of the metaphorical rope pulling you off your normal centre. Let it be so in good faith, even for a short time.

My real sympathy on this hike is with the agnostic and non-religious reader. By virtue of the very subjects under consideration this climb will take you on paths very seldom trodden. From you I ask a very special trust and patience. Having said all that, I do not doubt that even religious readers will also find certain sections a stiff scramble. We are a recalcitrant breed of mountaineer – scrupulous over our maps and hi-tech gear – but unfamiliar with vast mountain ranges beyond our neighbourhood. Poor us! With titans like Schuman and Columban, we will be forced to breathe the thin mountain air of Catholic ascetics, and even have some cherished, Protestant myths about the Celtic church overturned. And the Catholic readers will have to suffer the interpretations and criticism of a sympathetic but non-Catholic pen. So again, my only plea is that you all have patience with the path I have paced out. I hold out my hands left and right. Let us climb together, grumbling where necessary but nevertheless keeping in step with our fellow adventurers – for I believe that the view is amply worth the journey. And if the reader disagrees after that then they can always give the book away to someone they don’t like for Christmas!

Enough, enough! Let us have done with all this Hibernian self-deprecation and close with Columban’s own words 1400 years ago;

‘If any of my words have outwardly caused offense to pious ears, pardon me for my treatment of such rugged passages…. And for the freedom of my customs, so to speak, was in part the cause of my boldness. For among us it is not who you are but how you make your case that counts…’

[1] "In proposing to relate symbolic language to self-understanding, I think I fulfil the deepest wish of hermeneutics. The purpose of all interpretation is to conquer a remoteness, a distance between the past cultural epoch to which the text belongs and the interpreter himself. By overcoming this distance, by making himself contemporary with the text, the exegete can appropriate its meaning to himself: foreign, he makes it familiar, that is, he makes it his own. It is thus the growth of his own understanding of himself that he pursues through his understanding of others. Every hermeneutics is thus, explicitly or implicitly." Ricœur, Paul, Charles E. Reagan, and David Stewart. "Existence and Hermeneutics." In The Philosophy of Paul Ricœur: An Anthology of His Work. Boston: Beacon Press, 1978, pp. 101 and 106.

[2] Paul Ricoeur, Memory, History, Forgetting

[3] Ibid

[4] He founded a monastery at here at Bobbio, whose library was one of the richest in Europe, and the setting for Umberto Eco’s famous novel, The Name of the Rose.

[5] “St Columban is one of the very great men who have dwelt in the land of France. He is, with Charlemagne, the greatest figure of the middle ages.” Leon Cathlin, poet, novelist and dramatist

[6] The full opening sentence of the letter is ‘O the holy lord, and father in Christ, the Roman [pope], most fair ornament of the Church, a certain most august flower, as it were, of the whole of withering Europe, distinguished speculator, as enjoying a divine contemplation of purity. I, poor dove in Christ, send greeting.’

[7] Columban is referring to the Apostle Paul’s metaphor of the church as the body of Christ in his first letter to the church in Corinth, Greece.

[8] He was acknowledged to be saint without reference to any posthumous miracles.

[9] Perhaps only because Columba of Iona’s work was all lost.

[10] These are now in the libraries in Turin, Milan and St. Gall.

[11] Article in the Irish Times by my friend Alexander O’Hara. Mar 17, 2017. ‘The first poem about Ireland by monk who inspired Heaney and EU’s architect’

[12] In Italy, Alcide de Gasperi and in Germany, Konrad Adenauer

[13] Following Heidegger’s lead H. G. Gadamer criticized Enlightenment thinkers for harbouring a "prejudice against prejudices”. Gonzalez, Francisco J, “Dialectic and Dialogue in the Hermeneutics of Paul Ricouer and H.G. Gadamer,” Continental Philosophy Review, 39 (2006), 328.

[14] Hans-Georg Gadamer (1900 –2002) was a German philosopher of the continental tradition, best known for his 1960 magnum opus Truth and Method (Wahrheit und Methode) on hermeneutics.

[15] Javier Solana (former Secretary General of the Council of the European Union, and High Representative of the Common Foreign and Security Policy) wrote this in his forward to Victoria Martin De La Torre’s wonderful book, Europe, A Leap into the Unknown.

[16] Columban’s 5th Letter

[17] It was the Theologian Robert Jenson who wrote ‘the world has lost its story.’